COVID-19 can only be controlled by social separation and careful personal hygiene. Many people will probably catch it, but only a tiny percentage of people will be severely affected.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

If we do not practice simple preventive practices, somewhere between 5000 and 25,000 people in Australia could die from COVID-19.

It is expected that the incidence of COVID-19 infections will peak this winter in Australia, and then fade to become endemic (a permanent feature of human virus infections) in the same way that measles and mumps were before vaccinations controlled them.

History of COVID-19

Coronaviruses are very common, and several dozen affect humans, usually causing a common cold or other minimal infection. This has not changed for millennia. Every species of land animal (mammals, reptiles, birds) has coronaviruses specific to that species. Problems only occur when the virus spreads to a different species.

This happened with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) a coronavirus spread from civet cats that started in Guangzhou, China in early 2003. It had an incubation period of three to seven days. Overall mortality rate with SARS was up to 15 per cent, but higher in elderly and chronically ill. The outbreak was contained by October 2003 because the infectivity was lower and the death rate higher than with COVID-19.

It is probable that in October or November 2019 someone in the wild animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, came in close contact with a bat and/or pangolin that was infected with a coronavirus specific to that species. That person became infected with this non-human strain of coronavirus, which then mutated to be able to live in humans. The infected person passed the infection on to others in contact with them, and the disease has spread worldwide from there.

In the Middle Ages, the bubonic plague also became a pandemic, and spread via rats from China to western Europe, but this is a bacterial infection, and can now be controlled by antibiotics, although it still occurs in some impoverished areas today. The spread of bubonic plague from China to England took about six years, as the fastest form of transport 500 years ago was a horse or sailing ship.

With modern transportation, the spread of infections can take merely hours or days from one side of the planet to the other. The world's last pandemic was the Spanish Flu in 1918-19.

The first doctors who raised concerns about the abnormal coronavirus infections in Wuhan were disciplined by the Chinese government for rumour mongering, and were silenced. Nothing happened for a month before the Chinese government finally acknowledged there was a problem, and started quarantining patients on December 31, 2019. This delay caused the worldwide spread to be worse and faster than it could have been.

Infectivity, and keeping safe

One person with COVID-19, on average, spreads the infection to 2.5 other people, which is the same infectivity as influenza. It can be spread by contact with the saliva, phlegm, tears, semen, vaginal mucous or blood of an infected person.

The virus can survive for many hours on a surface; the most common way to be infected is to touch a surface that has been recently touched by an infected person.

This is why hand washing is so important. Soap and water are just as effective as a 60 per cent alcohol hand wash, but washing for at least 20 seconds is advisable.

To catch COVID-19, you need to be in a social situation (about one metre away) with an infected person for 15 minutes or more, touch something that an infected person has recently touched, be in close contact (e.g. within 30 cm) of an infected person for two minutes, or in direct contact with any of their bodily fluids. A person with COVID-19 who touches their face (tears, saliva, phlegm) and then shakes another person's hand, can easily pass on the infection. Kissing is obviously very risky.

Surfaces that have been touched by a person who may be infected should be cleaned with an alcohol solution or any common household cleaner. The coronavirus is not able to survive exposure to soap, alcohol, cleansers, temperatures above 27°C, or direct sunlight for five minutes as these all rupture the protective capsule that surrounds the virus. Dry and metallic surfaces are less likely to harbour the virus than moist or permeable (e.g. wood) surfaces.

Symptoms

The incubation period is four to six days, meaning that if you come into close contact with an infected person, it will be that time before you show symptoms if you catch the disease. There have been reports of longer periods of incubation, which is why a 14 day quarantine is considered the standard to be safe from spreading the infection.

The symptoms of COVID-19 are similar to those of a common cold or influenza, but with less nasal symptoms than a common cold. A sore throat, fever above 37.6°C (usually above 38°C), hard dry cough, tiredness, shortness of breath, chest pressure and loss of smell occur. Diarrhoea and loss of appetite are less common symptoms, and are usually mild.

In severe cases, the lungs become choked with mucus, it becomes hard to breathe, and secondary infections may occur.

In the rare cases where death occurs, it is usually due to sepsis (generalised blood infection), lung or heart failure. It is not always possible for a doctor to differentiate between influenza and COVID-19 on clinical grounds, and further testing is necessary to be sure of the diagnosis.

It is probable that the vast majority of people who catch COVID-19 will have no or minimal symptoms. Because testing is not universal, it is certain that far more people than reported have already caught the virus.

This makes controlling the spread of COVID-19 very difficult, and it is probable that most of the world's population will become infected in the next year or two, but only a minority will show symptoms; a small percentage will become significantly ill; and a tiny percentage will die.

Testing for COVID-19

Testing for COVID-19 is currently restricted, even in Australia, because there are not enough test kits available, so only those most likely to have the infection, and meeting specific government criteria, are being tested.

Even so, Australia has one of the highest rates of testing in the world, and the criteria for testing are being steadily eased to allow more and more people to be checked. You cannot get a test from your GP or a hospital, just because you want one.

The test involves taking a swab from the nose and/or mouth, and the result is available after 48 hours, although faster tests giving results in less than an hour are due to arrive soon. On average, only one in every 100 people tested in Australia has returned a positive result.

Developing countries are in a worse situation as the tests are expensive, and very few people are being tested. As a result, it is certain that COVID-19 is far more widespread than shown by the statistics released by each country.

Mortality rates

The statistics show a 2 - 3 per cent mortality rate (the rate for influenza in 0.1 per cent), but this is for the minority affected who have significant symptoms and have been tested positive.

The overall mortality rate from COVID-19 for everyone who has any form of the infection may well be one-tenth that of the reported rate.

Because of more widespread testing than most countries, and more affected people being detected, the death rate in Australia is only 0.3 per cent at present, one of the lowest in the world.

Older people, smokers, and those with poor immunity due to cancer treatment, diabetes, lung or heart conditions are far more at risk than young healthy people.

It is highly unlikely that someone who recovers from COVID-19 will catch the infection again. Most viral infections give medium to long term immunity against re-infection (e.g.: you only catch measles once).

Those with an immune deficiency (e.g. splenectomy, chemotherapy) may not be able to produce the antibodies to give long term immunity, and will need to take prolonged precautions against infection.

Vaccination

It is unlikely that a reliable vaccine will be available until the middle of 2021 or later, and then there will be further significant delays with manufacturing and distribution.

It is more likely that antiviral medications, being developed to treat SARS, will be further refined and made available to treat COVID-19 before a vaccine is available.

Antivirals are not available for most viral infections, but this pandemic has boosted research funding dramatically, and laboratories in many parts of the world are now working 24/7 to develop an effective antiviral against not only COVID-19, but all coronaviruses.

This is not just an altruistic aim, because the company/university that is first able to develop an effective coronavirus antiviral medication or vaccine will make an enormous amount of money.

The influenza vaccine will give no protection against COVID-19, but a person suffering from influenza will have their immune system compromised, and be more likely to catch COVID-19, and will suffer more serious effects from it. Get your influenza vaccine this year when it becomes available in early April.

Treatment

For the majority of those who develop a COVID-19 infection, the only treatment would be a mild anti-inflammatory/analgesic (eg. ibuprofen - Nurofen), zinc lozenges (zinc acts in the throat to slow viral reproduction), isolation to prevent transmission, and rest.

The treatment for those who are more seriously affected is limited. Experimental antivirals, hydroxychloroquine and other autoimmune suppressants, salbutamol inhalations (e.g. Ventolin) and bromhexine mixture or tablets (e.g. Bisolvon - liquefies sticky mucus) are the first steps.

If hospitalised, oxygen, pulmonary lavage (sucking mucus out of the lungs through a tube passed down the throat into the lungs) and forced ventilation may be necessary.

Children seem to be less affected, in a similar way to how the Epstein-Barr virus that causes glandular fever usually only causes a serious illness after puberty. Several viruses seem to be far milder in pre-pubertal children than in adults. Although they show minimal or no symptoms, infected children can still pass the infection on to others.

Face masks and personal protection

Face masks are very important on people with any viral infection to prevent the spread of the virus but are of minimal benefit to those who are not infected, unless they are in prolonged very close contact with an infected person (e.g. doctors, nurses).

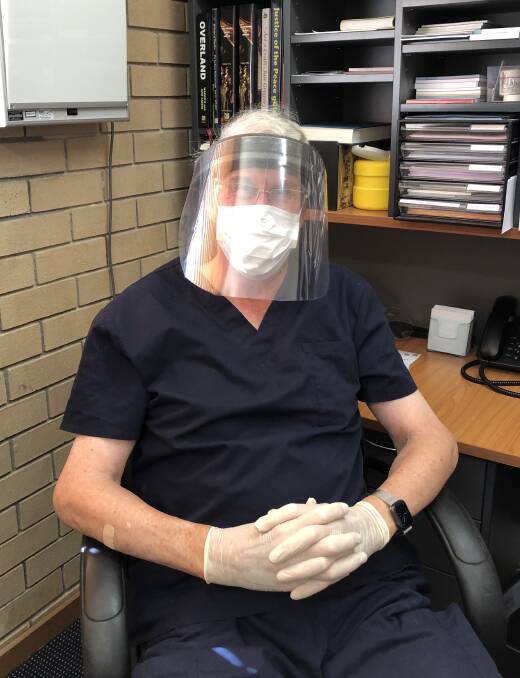

PPE (personal protection equipment) includes masks, goggles or shields, gloves and special gowns. They are used by health care workers who are in continual close contact with infected patients, but unfortunately there are currently insufficient supplies for GPs attending suspected cases to use all these, so most are using only masks and gloves at present.

Seeing a GP

If attending a GP with flu-like symptoms, and particularly with any recent history of overseas travel, notify the GP practice when booking an appointment.

The present protocol for GPs is that the patient phones reception from their car when they arrive; the GP will wear a mask and gloves while attending the patient in their car, take the patient's temperature immediately, ask some questions, and possibly undertake some minor examination.

If the GP believes the patient does not have COVID-19, the patient will be taken from the car into the practice for further examination.

If there is a suspicion that the patient may have COVID-19, the patient is not taken into the surgery, but swabs are taken by the GP, the patient is referred to a nominated pathology collection centre for testing (same protocols as at GP are followed) or the patient is referred to a hospital fever clinic.

Home isolation is essential until results are available.

Dr Warwick Carter has been a doctor for nearly 50 years. He has written 24 books, numerous newspaper and magazine articles, had his own radio and TV programs, and is a Fellow of the Australian Medical Association.